Resonant Standing Waves Comprise the Electron

by Calla Cofield for the Physical Review Focus

February 21, 2008

Link: Coherent Electron Scattering Captured By an Attosecond Quantum Stroboscope

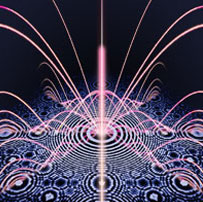

In a flash. To capture an unblurred image of a hummingbird, you can flash a strobe light at the same frequency as its fluttering wings. A similar "stroboscope" method uses sub-femtosecond light pulses synchronized with an oscillating laser field to repeatedly ionize electrons at the same moment in the laser's cycle and get clean images.

Researchers have recorded snapshots of electron motion at close to the particle's own natural timescale, which is less than a femtosecond (10-15 seconds). The experiment combines ultrashort light pulses with steady laser light to extract an electron from an atom in a controlled way. With control over the precise moment of extraction, the team was able to cleanly image the electron's quantum state, as they describe in the 22 February Physical Review Letters. This technique could help researchers probe electron-atom interactions in more detail and begin using electrons to observe atoms in the poorly-understood state following ionization.

One technique for controlling electron motion uses the strong, oscillating electric field of an infrared laser to ionize a cloud of atoms. During each cycle, the field points up, then down, then up again, so it can pull an electron downward and then slam it back up against its atom. The electron scatters off its atom and is then yanked to the right by a steady, sideways electric field, toward a detector. The detected positions of many electrons create an image of the electrons' motion during scattering and also provide information on the state of the recently-ionized atom.

But this technique lacks precision. From an electron's point-of-view, the laser field oscillates slowly, and it pulls electrons from atoms during a range of times near the moment of peak field strength, rather than releasing them all-at-once. So the resulting image on the detector is fuzzy and represents electrons in a variety of scattering conditions.

Now a team led by Anne L'Huillier and Johan Mauritsson of Lund University in Sweden has combined this laser technique with precisely timed trains of ultrashort light pulses to cleanly image electron motion. The pulses in the train were just three hundred attoseconds (10-18 seconds) long. The researchers synchronized the pulse train with the oscillations of a relatively weak infrared laser, so that their cloud of helium atoms received a strong, ionizing "kick" at a precise time during each laser cycle. Each attosecond pulse released a few electrons, some of which were thrown back against their atoms before being pushed sideways and detected.

Accumulating data from many ionization events, the team created clean images of the quantum state of electrons ionized at a single moment in the laser oscillation cycle. The images are the first of their kind that show such controlled electron-atom scattering. The team calls their system a stroboscope, after another device that uses periodic flashes of light to capture a still image of a hummingbird's wings, for example.

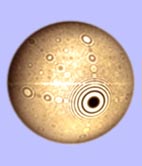

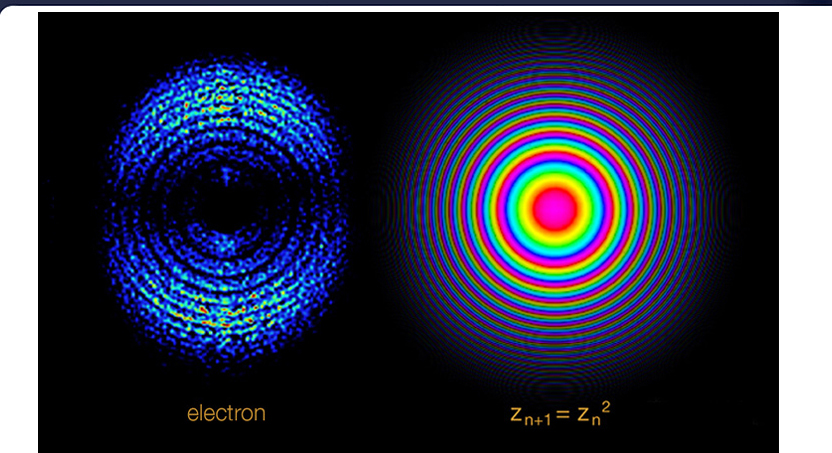

Each experiment generated a "bullseye" pattern showing the locations in which electrons struck the detector plate. To demonstrate that each image represented precisely one moment during the laser cycle--rather than a range of ionization times--the team shifted the timing of the attosecond pulses with respect to the laser field cycle. If electrons were ionized at a time when the laser field gave them an extra boost upward, the pattern shifted upward; if the ionizing pulse came a half-cycle later, the bullseye shifted downward. This pattern shifting wouldn't have been possible with longer-lasting ionization periods.

The next step will be further controlling and studying electron-atom interaction in more detail, says team member Kenneth Schafer of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. He also hopes researchers will use electrons scattered off their atoms to observe the unsettled state of atoms immediately after ionization.

Louis DiMauro of Ohio State University in Columbus is impressed by the demonstration of precisely timed ionization and imaging. There's really no other experiment where you can visualize rescattering," he says. "These are the sorts of experiments that demonstrate that if you have these attosecond pulses you have unprecedented control over electron dynamics that we didn't have before."

Analysis

The quantum stroboscope's images of the electron are a first glimpse into the subatomic realm. The nonlinear concentric rings comprising the electron's structure display the unmistakable Fibonacci order expressed in the quadratic function [ zn+1 = zn2 modulus n ], pictured above. This sacred mathematical structure is reflected as a standing wave pattern of resonance existing on all scales of the cosmos, in individual electrons, in crystals of calcite, in giant pyramids, all planetary bodies, and even underlying the form of galaxies.

This precise geometric formula appeared in the fields on Lurkley Hill, in Lockeridge, England in 2005 and again in a larger formation in Wayland Smithy in 2008. This fractal equation is closely related to the Mandelbrot Set, [ zn+1 = zn2 + c ]. First rendered by French mathematician Benoit Mandelbrot in 1980, this formula appeared in 1991 in the wheat fields of Ickleton, England.

The multitude of standing wave resonance maps presented throughout this site were rendered using these sacred formulas, which are keys to the nature of human consciousness and the changes culminating in the coming events of December 22, 2012. The revelation of the structure of the electron is but one in a series of profound discoveries that will altogether transform the human experience on this planet.